Submitted by ARASAllison on

“In view of the importance of the halo in art and considering the extensiveness of its use, it is curious to find so little agreement of opinion as to its origin and meaning, since it has been variously described as a symbol of the fire-worshippers of the East, as a decorative device, as a diadem, as a visible sign of the light and glory of God, as a protection from bird-droppings, as the disc of the sun and as the hvareno of the Persian.” - E. H. Ramsden

As Ramsden stated above in 1941 when he wrote for the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, the origin of halos has been mostly undecided. In my research on the topic, I argued that as a symbol or icon, halos are directly related to natural-occurring halos we witness in the skies. Empirically, halos are not distinctly tied to one religious faction or another. They appear all over the world and have been around for many centuries.

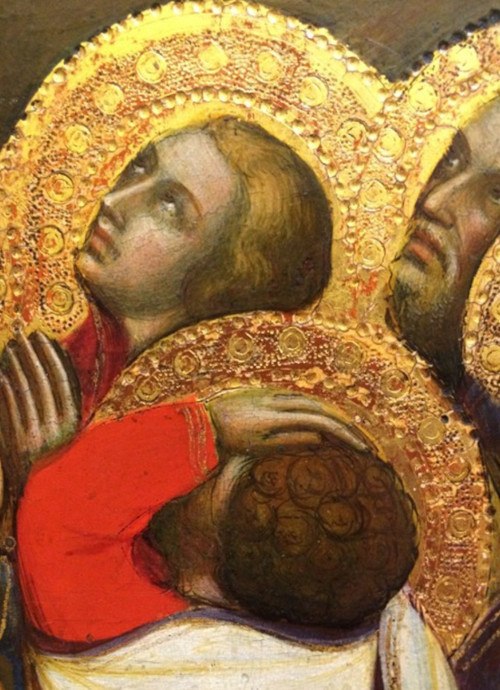

At first my curiosity about halos came from how awkwardly they were included in art during the Medieval and Renaissance periods. They at times occlude the faces behind them, hover flatly above or slice directly through heads. One can only imagine the clanging noises halos made when all saints turned their heads at once. Regardless of their clumsy inclusion and sometimes awkward profiles, they remained an important ingredient in sacred paintings. My dissertation titled “A Closer Look at Halos in Medieval and Renaissance Italian Art” explored the function of halos as a symbol that carried far more individual identity to the person wearing it than what we today might understand.

As it turned out, research revealed to me that it was mostly in Italy that halos were so diversified. Typically, halos are round and are either presented as a solid plate, a ring of light or a crown. Sometimes facsimiles of halos appear composed of vegetation, fabrics or architecture. When vegetation is woven together it’s called pleaching. In Italy, artists evolved from the dictated codes given by the church’s scholars and clerics for how a halo should appear and bloomed eventually into the personal styles that today help us properly identify the artist and the date of the art. Halos also held symbols within them to identify the virtues of the person standing beneath. Extra filigree and tracery introduced by prominent Sienese and Florentine artists allowed them to brandish their personal mark by using specific tools to pound texture into gold. In short, there is a world of information given to us in the shapes and styles of halos that I’d like to reveal. Additionally, I’ll give examples of how natural halos have been the prototype for halos in art, specifically in Italian Medieval and Renaissance art.

Read Halos in Medieval and Renaissance Italian Art in its entirety here.